Old Shasta Town A Semi-Ghost Town

Story and photos by Stacy Fisher

When the region around Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California caught gold fever in 1848, news spread like greased lightning,  attracting large numbers of potential prospectors who journeyed from afar to make their fortunes in the streams and rich mines of gold country. By the tens of thousands European immigrants also resolved to try their luck in the gold fields alongside their American counterparts.

attracting large numbers of potential prospectors who journeyed from afar to make their fortunes in the streams and rich mines of gold country. By the tens of thousands European immigrants also resolved to try their luck in the gold fields alongside their American counterparts.

Few were successful.

Pioneer Pierson Barton Reading had originally moved to upper Sacramento country from his native New Jersey (although in later years, he proclaimed Pennsylvania as his place of birth), where he made his living as a hunter and trapper along the streams of the district now known as Trinity County. Reading resided on his modest ranch and was known by his urbane and gracious manners.

In 1849, Reading discovered gold in the Clear Creek area of Tehama County, employing 60 Indians in the undertaking. He used his newly obtained wealth and subsequently founded Reading Springs, later renamed Shasta in 1850.

Situated in the Klamath Range foothills six miles west of Redding on Highway 299, the town became an indispensable commercial center and major shipping hub for mule trains and stagecoaches serving the settlements of northern California.

California’s ongoing gold fever extended beyond Sutter’s Mill with another wave of gold-seekers, many of whom set up camp in Shasta. The town was within easy access to plentiful natural springs, streams, and commercial resources. Nicknamed the “Queen of the Northern Mines,” the picturesque town was the focus of trade and social activity for thousands of miners and their families, expanding in its heyday to 3,500 residents.

By 1852, more than $2.5 million in gold had been discovered near the booming town, which had grown from tents, small buildings and lean-tos to family residences, saloons, barbershops, hotels, stores and assay shops. In that same year in December, fire destroyed the majority of buildings, which were quickly rebuilt, only to burn to the ground again six months later. Merchants responded by building a row of fireproof brick buildings, but the town’s economic vitality was already in decline.

When gold claims were depleted by the late 1860s, and its lucrative stagecoach and freight business relocated to nearby  Redding, merchants abandoned Shasta and the town fell into disrepair.

Redding, merchants abandoned Shasta and the town fell into disrepair.

In 1868, Pierson Reading died at his residence. A notice in the San Francisco Bulletin stated that Reading was “one of the oldest and best known American citizens of California.”

Fortunately, starting in the 1920s, a number of groups including the Native Sons of the Golden West, and the Shasta Historical Society recognized the historical importance of what had become a semi-ghost town and decided to preserve its heritage by restoring some of the remaining buildings. Mae Helene Bacon Boggs, who had grown up in Shasta as a little girl, led the endeavor. Boggs donated her extensive art collection to purchase a number of dilapidated properties.

The California State Parks Commission acquired additional properties in 1937, and the Shasta Courthouse was renovated to its 1860s appearance and reopened in 1950 as a museum, showcasing a huge assortment of fascinating artifacts that recall the early days of Shasta.

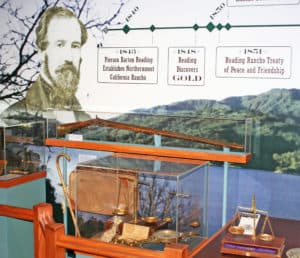

The refurbished Shasta Courthouse is central to the Shasta State Historic Park site. Visitors enter the courthouse into the reception area that’s also the location of the gift shop. A timeline of former Shasta history begins and continues through the museum, containing numerous authentic items of the Old West.

“It’s the overall introduction to the museum’s many attractions and what the park has to offer,” states Lori Marlin, Cascade Sector Superintendent, Department of Parks and Recreation. “The timeline takes visitors through the town’s history and its founding by Pierson Reading,” among other notable names. Items include vintage clothing, portable gold balance scales that miners would take with them into the field, as well as displays describing the first people in the area, the native Wintu, along  with a few of their artifacts like woven baskets.

with a few of their artifacts like woven baskets.

Other sections of the courthouse include the old courtroom that’s furnished with many of the original articles that tell the story of justice served in a bygone era.

There’s also an impressive art room, The Williamson Lyncoya Smith Gallery, showcasing a fine collection of urban California art, comprising paintings, an ornate piano, and household ornaments and decorative items.

The Sheriff’s Room features glass cases displaying an assortment of antique rifles and firearms that were typical of the day.

Downstairs, visitors can view the old jail section that holds four steel cells, along with wanted posters, a hangman’s noose, ball and chains and leg shackles.

Out in the yard behind the courthouse is a replica of a gallows built to recreate the last double hanging in the town of Shasta in 1874. “They would only build a gallows when someone was to be hanged, then tear it down afterward,” Lori reveals.

In addition, “There’s an old barn in the field behind the building that holds old agricultural and mining equipment that  people can inspect, plus two old cemeteries, and a day use picnic area,” all within walking distance of the courthouse.

people can inspect, plus two old cemeteries, and a day use picnic area,” all within walking distance of the courthouse.

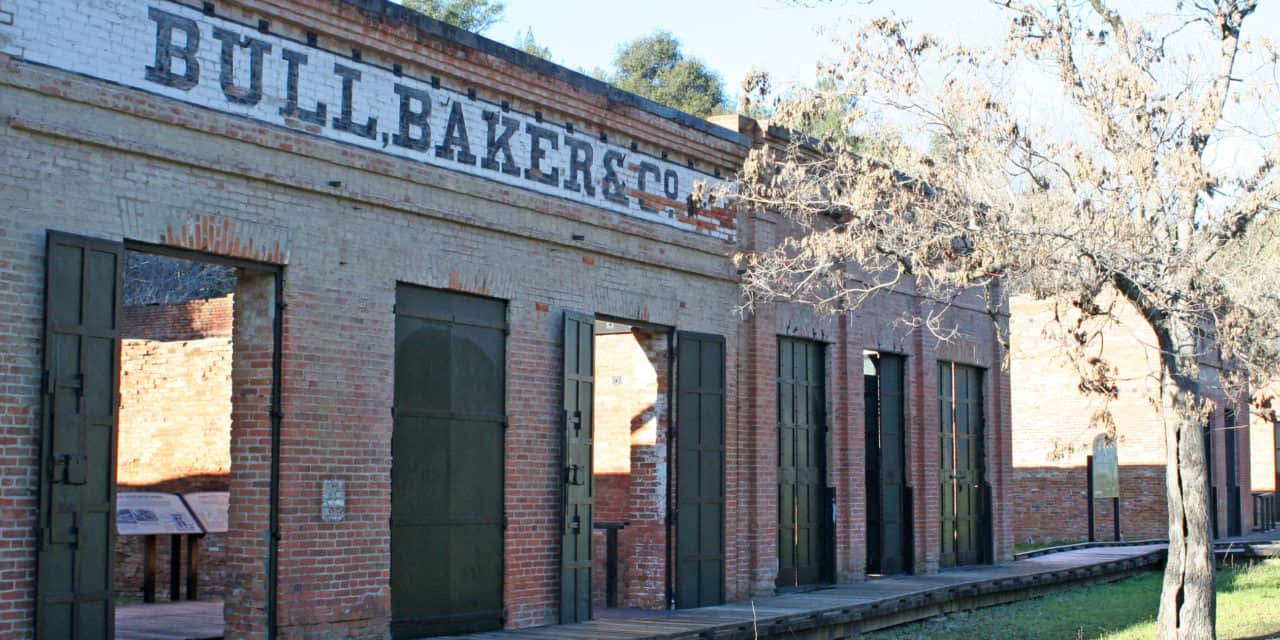

Across the street from the courthouse, the half-ruined, 1850s-era red brick buildings still stand as tribute to what had once been a bustling exchange. A blacksmith shop and a general mercantile store have been reestablished for visitors to stroll about.

The park is open 7 days a week and is free for folks to wander at their leisure. Entrance fee for the Shasta Courthouse Museum is just $3 for adults and $2 for kids, and is open Thursday through Sunday from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. Individuals and schools can contact the park service at 530-243-8194 for field trip opportunities and information.