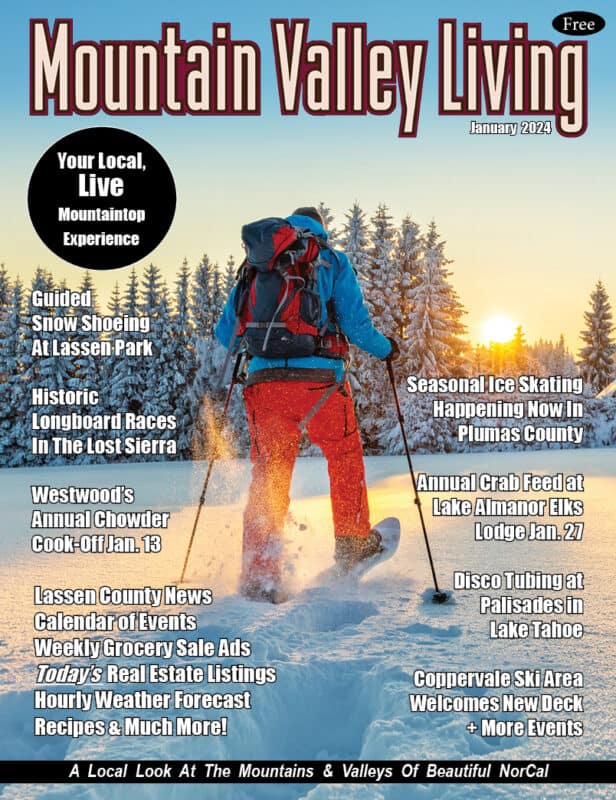

By Stacy Fisher

Photos by Dan Dobyns

[media-credit name=”Dan Dobyns” align=”alignleft” width=”300″] [/media-credit] With the fire season in California starting earlier this year partly due to the ongoing drought, the state’s firefighting personnel are on constant high alert for the next fire battle zone. Already numerous firestorms have raged statewide, bringing destruction to several suburban and mountain communities and destroying thousands of acres of wildlife habitat in the process.

[/media-credit] With the fire season in California starting earlier this year partly due to the ongoing drought, the state’s firefighting personnel are on constant high alert for the next fire battle zone. Already numerous firestorms have raged statewide, bringing destruction to several suburban and mountain communities and destroying thousands of acres of wildlife habitat in the process.

The definition of hero is easily descriptive of the firefighting crews called Hot Shots, who risk their own welfare to help protect the rest of us from the threat of wildfires. No matter the risk, these specialized teams are well trained to meet the challenges inherent in tackling destructive conflagrations.

Dan Dobyns of Westwood is stationed in Susanville, and has been at the frontlines in the fight against wilderness fires for 11 seasons as a Hot Shots crewmember.

“I started as part of a contract crew—the Eagle Strike Team out of Reno, Nevada,” Dan recalls. “It was the day after my 18th birthday that I went to Arizona on my first fire. And then I contracted with the Bureau of Indian Affairs for my second season of fighting fires. After that I went to Ruby Mountain Hot Shots in Elko, Nevada where I spent two more seasons. Finally I joined Diamond Mountain Hot Shots in Susanville in 2008,” overseen by the Bureau of Land Management.

Hot Shots tend to specialize in fighting aggressive wilderness fires, as opposed to city-based firefighters who normally attack structure fires that endanger homes and other buildings within metro areas. Typically, Hot Shots often play a critical role as first responders, but not necessarily. Anywhere crews need additional manpower, Dan says, the Hot Shots can be called in to assist.

Hot Shots are an all-risk management resource, he continues, “so if we’re needed we’ll go to natural disaster areas, for example after Katrina hit in 2005, I traveled down with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to help with hurricane relief efforts.”

Often joined by additional Hot Shots teams or regular fire crews from other states or locales, Dan says “we can find ourselves working very long shifts, “because fires are always evolving, never staying the same.” Hot Shots may find themselves fighting a fire for 24 hours straight or more, if they’re the only manpower available at a given location. “We do have rest guidelines, but those rules are flexible when the situation requires human resources and there’s no one to relieve us.”

Hot Shots crewmembers are generally comprised of younger people with a lot of stamina to do the backbreaking work of fighting fires. But ages can range from 18 through 50s in some cases.

“Initial training starts with a prerequisite course, which covers the basics in fire-fighting techniques,” Dan explains. Training is ongoing, with a number of classes provided every year throughout the winter when the dangers of wildfires are less, and Hot Shots can upgrade their qualifications. “We learn new protocols, new tactics and technologies, and hear about new legislation that affects our work duties.”

In California there are a total of 44 Hot Shots crews. Nationally there are 109. There’s a minimum of 18 to 25 individuals who make up a typical squad.

Hot Shots will, on occasion, camp out in wilderness areas where fires might be expected to erupt. “We sometimes preposition our crews in districts where fires are expected, if that district deems they have a high likelihood of fire in the near future, for example, when there’s a forecast of lightning in a dry area.” And with a severe drought affecting the entire state, there’s no lack of dry areas to protect.

Quick response time is critical. “When a fire is reported we get a radio message from dispatch providing a report that includes basic information, such as the location of the fire, best route to travel, and type of fire. My immediate supervisor will also get a call on his cell phone with an order to assemble the crew and start an action. Wherever we might be, we drop everything, pick up our gear at the station, load up the vehicles and head out, sometimes to catch a plane to the fire site in a distant region or another state altogether.”

The complexity of a wildfire requires a planning process before a fire crew can be sent out. At the local level, the Fire Management Officer is responsible for coordinating the operation within his local district. He decides what resources are needed for a particular fire. With bigger fires that are more multifaceted, an Incident Command Team is brought in to oversee the operation.

A command center is set up in a safe area in the nearest town where a fire is nearby, like elementary schools or wherever it is deemed safe. “A safety zone is any place where we can remain without having to use our fire shelters, such as the shoreline of a lake or an area deficient in combustible material.”

The Operations Section Chief oversees the operation from the command post under the auspices of the Incident Commander. He receives intelligence and progress reports from the field on what daily objectives are being accomplished or not.

Dan became interested in fighting fires when he was just eight years old, living in Loyalton, California. “One day in 1994, the Cottonwood Fire broke out in the Tahoe National Forest at the Cottonwood Campground in Sierra County,” Dan recalls. “Numerous firefighters were around our house.” As an impressionable kid it was one of those dramatic moments in life that stuck with Dan. “Ever since then I decided I wanted to fight wilderness fires.”

The dangers of fighting fires are mostly obvious. When Hot Shots are sent into remote areas, they have to diligently keep an eye out for flaming trees that may fall at any given moment, as well as heavy winds fanning furious flames that could potentially overtake them.

“Constant communication is essential when you’re in the field,” Dan says. “Any breakdown in communication is when things start to go wrong. That’s always part of the planning.”

The Hot Shots team includes a highly experienced firefighter who works as a lookout. “He’s the one who walks the fire line, looking at what’s in front of us and behind us, and making sure where we’re going is safe. He watches what we call our ‘back door,’ which is the best escape route to our safety zones should a fire appear ready to overtake us.”

All firefighters who are positioned on the front lines carry mandatory, lightweight fire shelters that they can deploy in emergency situations as a last resort. The shelter is a lightweight pup tent made of fiberglass and aluminum enclosed in a small pouch that can be used as a protective cocoon in a life-threatening predicament. The fire shelter reflects radiant heat, reducing a deadly 1,000-degree fire to a survivable 120 degrees for a few minutes, while providing a temporary pocket of breathable air in a fire-entrapment situation.

The Hot Shots use basic tools in the field, which include chainsaws and shovels, along with radios for communication and handheld GPS devices. “At night, we have help from helicopters flying overhead with infrared to provide accurate mapping, and that information is then relayed to the command post,” adding that crews can have all the gadgets in the world, but it all comes down to hard work, often battling fires along steep hillsides or rugged terrain.

If the team is in a remote region that prevents them from re-supplying themselves from a nearby location, the fire service will drop supplies from helicopters using GPS coordinates that are radioed in. “Sometimes we’ll have to clear an area for the helicopter to land,” Dan says.

A situation can be dynamic and ever changing, so plans must keep evolving, too. When a fire suddenly switches direction and is threatening a housing track, for example, a new plan must be formulated to protect homes from the advancing flames.

The drought is unfortunately expected to greatly increase the likelihood of a severe, widespread and longer lasting fire season this year and for the foreseeable future. “When you’re not seeing a healthy snow pack, you know trouble lies ahead,” Dan laments.

Dan is obviously very passionate about his vocation. “It’s never the same. You’re always traveling; it’s always different. The hardest part of the job is leaving my family for up to 28 days at a time. But once I return home safe and sound, it feels good that I accomplished something important.”

When he’s not in the field fighting fires, Dan likes to go camping, relax, play at the lake, and spend quality time with his wife Mara and one-year-old daughter Vivian.

“Some people will come during a summer or two and work on the fire line to make some money for school,” Dan says. “For other people like me who really stay year after year, it’s not just a job anymore–it’s a lifestyle.”