A Civil Man: The Story of Ishi By Stacy Fisher

A Civil Man: The Story of Ishi By Stacy Fisher

The sound of barking dogs first alerted the slumbering slaughterhouse butchers that a stranger had found his way onto their property. Jolted from what was likely a deep sleep, they dressed and went outside to investigate the cause of all the commotion. What they found, or rather who they found, was a man crouching alongside the corral fence, trembling from the early morning cold, emaciated and starving. They called off the dogs and quickly phoned the sheriff of Oroville, located just a few miles away.

It was the 29th of August, 1911 to be exact, when Sheriff J. B. Webber arrived with his deputies, guns drawn menacingly, and discovered that the frightened man was an Indian, at the limits of exhaustion, and wearing only a small piece of ragged canvas to protect him from the elements. Since he spoke no English, the sheriff drove the weary stranger to the county jail in Oroville to protect him from the curiosity of local townspeople, who he expected would soon pour in to see the spectacle of a ‘savage’ in their midst.

Ishi, as he would subsequently become known, had meandered his way alone through miles of harsh countryside from what is now the area around Red Bluff, California, to the south and into Butte County, where he faced an uncertain future and expecting death at any moment.

When local and national newspapers revealed to the world the last remaining “wild” man had been discovered — a Yahi Indian, thought to be the sole remaining survivor of the Yana tribe — interest in Ishi became widespread. He had wandered out of the wilderness near the foothills of Mt. Lassen and into the 20th Century.

In her seminal book, Ishi in Two Worlds, Theodora Kroeber describes a man not of primitive savagery, a common ill-informed stereotype of the day, but of a simple, yet civilized man. Her husband Alfred Kroeber, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, and a leading authority on traditional American Native history and cultural, along with his colleague, UC Anthropology Museum Director Thomas Waterman, took a keen interest in Ishi’s welfare.

Yahi translator Sam Batwai set upon translating what he knew of Ishi’s language, which differed substantially from the three other subgroups that made up the Yana nation.

Eventually, it was Kroeber who named him Ishi, meaning, “man” in his native tongue.

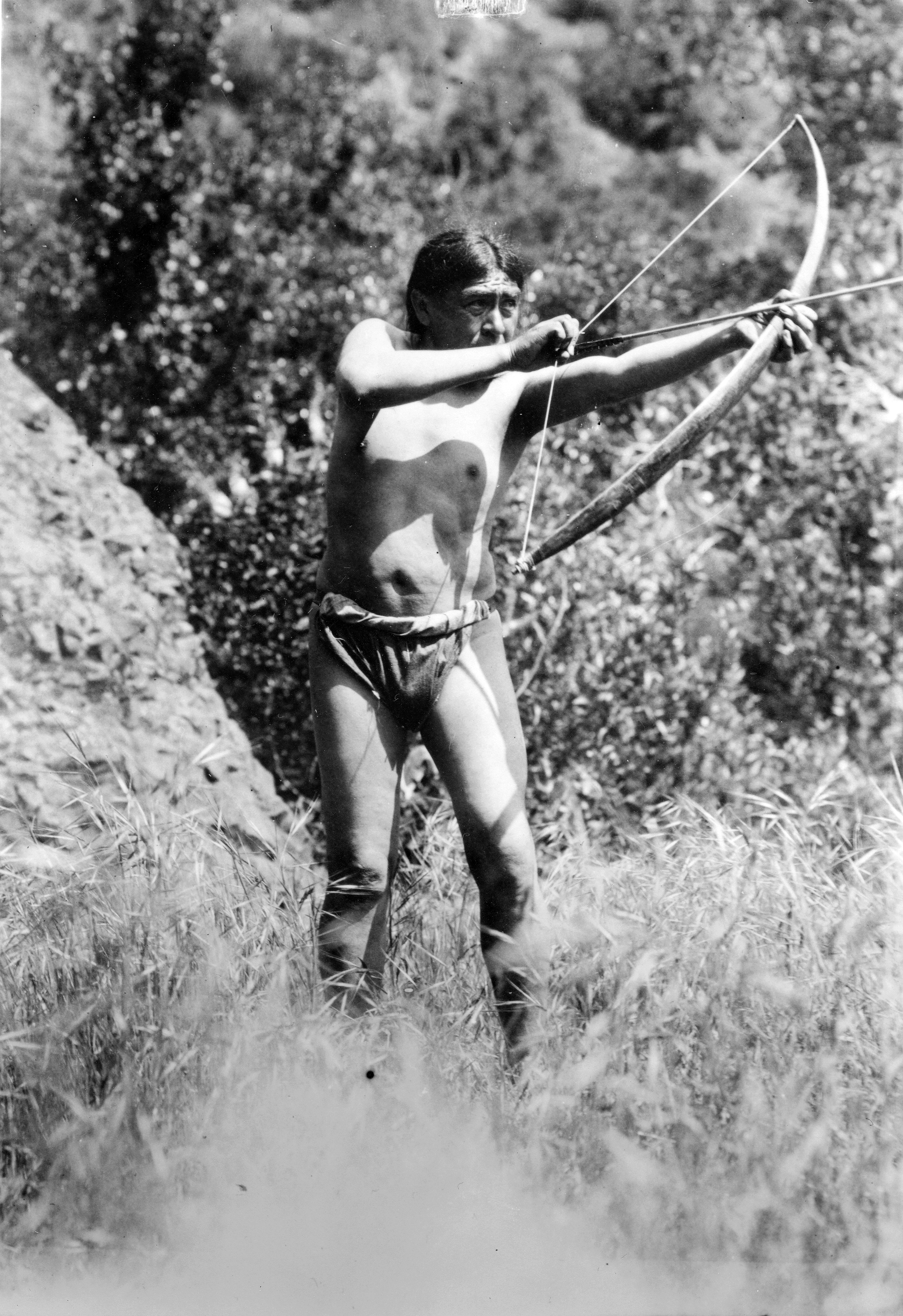

For nearly five years, Ishi lived at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology where he and Waterman became close friends. Several thousand visitors to the museum observed Ishi demonstrate arrow-making and other aspects of his tribal culture. Although employed at the museum as a janitor, Ishi was free to construct artifacts, many of which he gave away to visitors.

The tragic loss of life and cultural destruction that befell innumerable Native American tribes led Kroeber to recognize that all traces of indigenous cultures would soon pass away forever. He and his colleagues routinely interviewed Native Americans from a variety of tribes, assembling vocabularies, taking photographs, and collecting artifacts.

Ishi was hospitalized in late November of 1911 for a respiratory infection, but his health soon improved, and so too did his understanding of English, which he was nevertheless reluctant to use.

Piece by piece, Ishi’s past was reconstructed and revealed to anthropologists Kroeber and Waterman. Both men recognized his vital link to cultural information about North America’s Native American history. According to Theodora Kroeber, the Yana struggled to maintain themselves by gathering acorns and foraging for berries, fishing the streams for salmon, and hunting deer and smaller game. It was often a hard and sometimes desperate search for food, with never enough to be found within their own borders, especially in the winter. She describes how the Yana would sometimes embark on raids into the lowlands of their neighbor’s territory to find additional food in the streams and forests, and this often resulted in fierce fighting with the Wintun in the Northern Sacramento Valley, or the Maidu to the southeast of Deer Creek who feared them the most.

When white settlers first reached the area, they had already heard of the Yana’s reputation for courage in battle, and the warrior’s tactics of speed and surprise. During conflict the Yana’s weapons were the identical implements by which they lived: bow and arrow, knife, rock and sling, and pointed spear. But such an arsenal would be no match against the rifle and Gatling gun.

An estimated 1,500 to 3,000 members made up the Yana nation previous to the 1840s, with the Yahi numbering around 400 individuals.

By 1849, the Gold Rush began in earnest, with miners and prospectors aggressively making claims to lands and streams once held since antiquity by Native American tribes. Farmers and ranchers also settled on large tracts of land, further pushing out indigenous populations.

In 1865, the massacres of the Yahi began with 74 killed in extermination campaigns, including Ishi’s father. A year later, the Three Knolls Massacre in 1866 claimed another 40 victims by vigilantes as part of a retaliatory attack for two white women and a man killed in Oroville, followed by the Dry Camp Massacre, with 33 killed. And again in 1871, the Kingsley Cave/Morgan Valley Massacre killed at least 30 more Yahi Indians. Another raid separated young Ishi from his sick elderly mother and younger sister to fend for themselves, as he barely escaped with his life. Subsequent attacks scattered the remaining tribe members throughout the Sierras.

A remnant band of Yahi, perhaps numbering no more than 25 individuals, including Ishi, concealed themselves between 1870-1911 in the Dear Creek and Red Bluff wilderness areas of Tehama County. One by one, each member succumbed to disease, starvation, exposure, and violence, until Ishi alone remained.

During the next few years after Ishi’s appearance, newspapers frequently wrote anecdotes referring to Ishi’s reaction to twentieth-century technological wonders. From airplanes to automobiles, to the use of electricity, gas stoves, telephones, flush toilets, and even doorknobs, the strange machinery of the modern world made a huge impression on him.

Fascinated by the unfamiliar sights and sounds of San Francisco, Ishi ventured out on a daily basis strolling the Bay Area, sightseeing and riding trolley cars on Russell Street, which he believed to be powered by powerful spirits. This world was kinder to Ishi than the world he and his people lived in just a few years earlier.

The various novel foods of this new world were also appealing to Ishi. Never had food been obtained with such ease in the wild. He bought groceries from a neighborhood store with his earnings from the museum, enjoying everything from bread and jelly, to coffee with sugar or honey, as well as meat and potatoes, rice, beans, and fruit. He also developed something of a sweet tooth and often carried candy with him.

Anthropologists at UC, Berkeley continued to record in detail the ancient techniques that Ishi demonstrated in tool-making, including woodcraft, fire starting, carved obsidian arrowheads, archery skills and hunting. He also shared his terror-frought memories of the various massacres of his people and his personal despair.

Ishi’s vast wilderness knowledge was substantial, and together with Waterman and Kroeber, they visited and mapped the Deer Creek area of Tehama County in the summer of 1914. Waterman remarked on Ishi’s “gentlemanliness, which lies outside of all training and is an expression of inward spirit.”

Ishi lived with the Waterman family during the summer of 1915 at their home on Cherry Street. He continued to impart his knowledge of tribal history, ceremonies, language, and culture to his dear friend, and also shared his love of song. Ishi especially liked to sing about animals, hunting, curing the sick, and performed dance as well. Ishi was a virtuoso of bird songs and wild animal calls; the growl of a mountain lion, the honking of geese, the plaintive wail of a coyote, or the distressed cry of an injured rabbit.

Telling intricate stories was an important part of Indian culture, and Ishi could tell stories for hours on end. Such oral traditions were how Native Americans would pass on information from one generation to the next. Famed linguist Edward Sapir recorded several of Ishi’s tribal stories and songs on a phonograph machine, but many of those records have since vanished or been destroyed by time.

Most of the chapters of Ishi’s life are lost forever, as are the histories of hundreds of California tribes who suffered at the hands of the white man.

By the turn of the 20th Century, most North American Indians had been assimilated into Anglo society. Still, full rights would not be granted to Native Americans until 1924 under the Indian Citizenship Act.

Approximately 560 federally recognized Native American tribes exist within the United States today. Fortunately there are some who strive to preserve Native American culture, so that as a nation we never forget the important role they have played in the history of this continent.

Ishi had no immunity to the diseases of modern civilization and was often ill. He died of tuberculosis in San Francisco on March 25th, 1916 at an estimated age of 54. In his coffin along with his ashes were placed his bow, a quiver full of arrows, a purse of tobacco, and dried deer meat.

In 2000, Ishi’s remains were returned from the city of Colma, California, to the Redding Rancheria and the Pit River tribes, to be laid to rest somewhere in the Northern California foothills of Mount Lassen and in concert with the traditions he cherished.

The power of Ishi’s legacy grips the conscience. He carried no animosity or bitterness towards anyone around him for the suffering of his people. His character epitomized forgiveness, good will, and kindness. By all accounts, he was the most civil of civilized men.