Western Pacific Railroad History

The Western Pacific was incorporated in 1903 to build from Salt Lake City, Utah and a connection with the Denver and Rio Grande Railway to Oakland, California. It was part of the Gould family of railroads that stretched from Utah to the Atlantic Coast with only a few small gaps. The WP was intended by both its East Coast financiers and its West Coast supporters and managers to provide a second transcontinental connection into central California, competing with the Southern Pacific Railroad and famously earning the ire of the mighty Edward H. Harriman, president of the SP, who vowed to prevent the WP from being built.

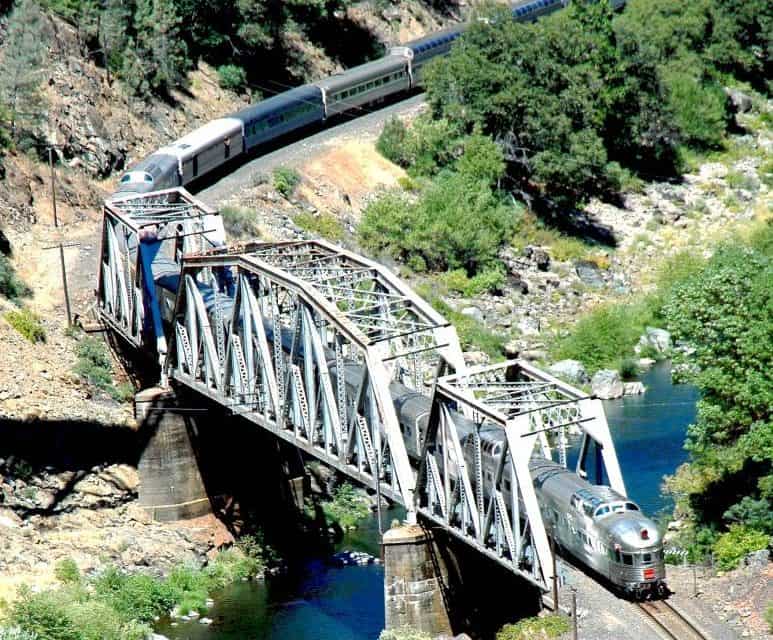

The railroad was completed in 1909 with the driving of a golden spike at the center of the Spanish Creek trestle at Keddie, California (near the city of Quincy). This trestle is now part of the famous Keddie Wye. By using the spectacular Feather River Canyon as its entrance into the Sierra Nevada range, the WP kept a gentle slope to its railroad and avoided the tremendous snow removal problems which rival Southern Pacific faced on its much steeper route over Donner Pass. So committed were the builders to maintaining a shallow grade to the line that they built the Williams Loop, where the tracks actually form a circle and cross over themselves, rather than violate the maximum dictated grade of 1 foot of rise in every 100 feet of linear run. The WP crested the Sierras at Beckworth Pass, the lowest saddle of the mountains, on the California-Nevada border. This well-engineered line allowed the railroad to move more freight with less power than the SP.

Such advantages, however, did not initially translate into success. The railroad’s charter forbid it to open branch lines and traffic levels were low. In 1916, the opening of the Panama Canal was the final nail and the WP went bankrupt. It was reorganized as the Western Pacific Railroad and, freed of the original restrictions, began acquiring feeder lines and building up its traffic base. Among the lines it acquired were the famous Sacramento Northern Railway and the smaller Tidewater Southern Railway, two electric interurban railroads in the fertile Central Valley of California.

In 1926, a financier named Arthur Curtiss James acquired control of the WP. James had major holdings in several large northern railroads, including the Great Northern. He saw the WP as an extension of the Great Northern into California, again competing with the mighty Southern Pacific. While the Great Northern built south from Washington State, the WP constructed a new line north from its Spanish Creek Trestle at Keddie, transforming the river crossing into the Keddie Wye, the most famous location on the railroad. The first 5 miles of this Northern California Extension (more commonly called “The High Line”) were the steepest and most expensive on the railroad, in some cases nearly 3 times as steep as the original mainline. The two roads met at the town of Bieber, California in 1931, completing the largest railroad construction project undertaken during the Depression.

As the WP was always overshadowed by its larger rival, the Southern Pacific, the smaller road learned to be innovative and frugal. While large, modern steam locomotives helped the road tackle larger freight cars, its original steam locomotives, outmoded they day they were built, continued in service until replaced by diesels. When the railroad needed new cabooses, it converted old, obsolete wooden boxcars and saved its money for revenue equipment.

When the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors introduced its FT diesel-electric locomotive in late 1941, the Western Pacific became one of its first purchasers and eventually became the first large western railroad to eliminate steam locomotives entirely. After World War II, the railroad completely modernized, becoming one of the first railroads to embrace such innovations as roller bearing freight car trucks, centralized traffic control systems, computerized traffic and inventory management, and turbocharged diesel locomotives.

The railroad also teamed with long-time partner Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, to operate the first passenger train designed around Vista-Dome passenger cars: the California Zephyr. These famous cars, with their 360 degrees of view in the upper dome section, were the trademark of the train. From 1949 to 1970, the CZ was the pride of the railroad, never downgraded in service even as it lost a reported $1 million per year by the end.

As fortunes rose and fell and the railroad industry changed, the Western Pacific found it increasingly more difficult to earn a profit. By the late 1970’s, mergers were folding many of the smaller railroads into larger systems. The trend finally caught up with the famous Feather River Route on December 22, 1982, when it was purchased by the Union Pacific Railroad along with Midwestern railroad Missouri Pacific. Soon, the WP image was quickly fading, although the UP generously aided many efforts to preserve the history of the railroad, including the establishment of the Feather River Rail Society and the Western Pacific Railroad Museum at Portola, California.

Today, the Salt Lake City to Oakland mainline serves the Union Pacific in conjunction with the once-rival Southern Pacific line over Donner Pass (the SP was later also purchased by the UP). The High Line, after years of neglect and low traffic, was later sold to the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad, which also acquired trackage rights from Keddie to Stockton, California. Now, more trains than ever roll over the former Feather River Route, confirming the foresight and vision of those people who helped build the railroad 100 years ago.